The latest in my Nigel Tranter re-read returns chronologically to the 15th century after my Montrose excursion. The story is told through the younger brother of the Earl of Douglas, who is close enough to the action to be a suitable narrator.

The book is set during the rule of James III of Scotland. He was born on May 10, 1451, and was King of Scotland from 1460 until he died in 1488. His reign was marked by internal strife, conflicts with influential nobles, and political instability. Yes, another feeble Stewart King.

He came to the throne on August 3, 1460, following the death of his father, James II, who died in a cannon accident during the siege of Roxburgh Castle. Perhaps unsurprisingly, James III wasn't much of a soldier, a significant weakness in a medieval King. His mother, Mary of Guelders, and several noble regents governed during his minority. He married Margaret of Denmark in 1469, which brought the Orkney and Shetland Islands as part of her dowry - probably the most significant achievement of his rule.

He was known for being more interested in the arts and astrology than in governance and warfare, which alienated many of his nobles. His reliance on low-born favourites and attempts to centralise power led to frequent rebellions. Notably, he faced significant opposition from his brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany, and John, Earl of Mar; the latter was probably murdered by him or his favourites. There was the inevitable fighting against the English, although they were otherwise occupied with the Wars of the Roses. The Lord of the Isles was also brought into submission after a campaign in the West Highlands. None of this fighting involved James in person.

Our hero, John Lord of Douglasdale, becomes the lover of James' sister, Princess Mary, who plays a significant part in the story. He does take part in all the conflicts and plots. His older brother became the somewhat more famous Archibald Bell-the-Cat.

The story reaches a conclusion at the Battle of Suchieburn on June 11, 1488. This was a substantial clash, little known even in Scotland. The battle took place near Stirling, close to Bannockburn, between the loyalists who remained faithful to the king and the rebels led by influential nobles who rallied around Prince James, who, albeit reluctantly, was placed at the forefront of the rebellion against his father. The battle concluded with a decisive victory for the rebel forces. King James was killed some distance from the battlefield. There are several theories, but Tranter goes for him, fleeing the battle, falling off his horse, and being murdered by Lord Grey.

This is one of Tranter's better stories despite the limited material with which to work. There are plenty of plot twists, and as it's a less well-known period of history, not one, you can always guess the outcome.

|

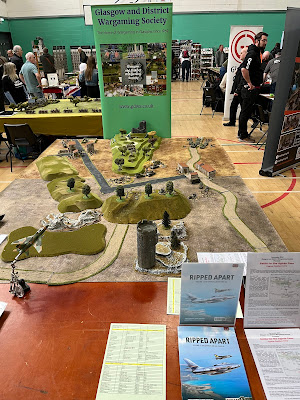

| Some of my 15mm Wars of the Rose figures of the period. |