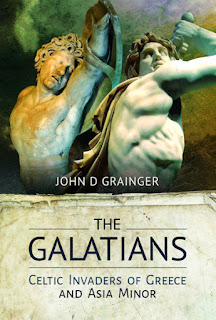

The Galatians are one of the lesser-known peoples of the Balkans in the ancient period. This may be because they had no written history of their own when the focus was on the Greek and then Roman impact on the region. John Grainger has written a very readable new history of the Galatians which pulls together what is known about these fierce warriors.

They bumped into Alexander the Great during his Balkan campaigns around 335BC when an agreement was reached on spheres of interest. With the Romans pressing the Gauls in Italy and the Dacians resisting their expansion to the north, they began to expand south-eastwards towards Thrace. Alexander’s death and the subsequent wars of succession created an opportunity, which the growing Galatian population exploited.

The Galatian method of warfare was the equivalent of the Scottish clans ‘Highland charge’. Very effective in open ground, but could be blocked in mountainous terrain and by cities, as they had little siege warfare experience. Later they developed a strong cavalry arm, which was probably constituted from the tribal elites while the foot increasingly came from subjugated peoples.

They invaded Macedon and Greece on several occasions, and while the Greek sources called these raids, it is likely that they were also looking for new lands rather than simple plundering. After being repulsed, they establish two loose states around the Scordisci and a new state in Thrace called Tylis. The latter lasted only sixty years or so while the Scordisci were an important Balkan power for three centuries.

One of the surviving groups from the wars against Macedon moved into Thrace and then across into Asia Minor, which was itself divided in a period of endemic warfare. The Galatians were initially used as mercenaries, going on to establish three separate tribal groupings in central Anatolia called the Tolistobogii, Tektosages and Trokmoi. While the Greeks called them barbarians, it seems clear that they abided by the diplomatic and treaty conventions of the period. Antiochos halted their further expansion at a battle known as the Elephant victory (269 or 268BC), which the Galatians had not met before. Despite this defeat, the Galatians were still a force to be reckoned with, raiding neighbours they didn’t have treaties, still primarily for settlement purposes and being used as mercenaries. Galatian cavalry was particularly sought after.

By the 2nd century, they were being squeezed between the Romans and Pontus in Asia and Roman expansion in the Balkans. This weakened their control of subjugated tribes, and both states went into decline, eventually becoming Roman provinces.

This is an excellent narrative history of the Galatians, perfect for the general reader who wants to know more about these extraordinary warriors who were also better organised and more effective diplomats than the ‘barbarian’ tag might imply.

For wargamers, it is another tabletop use for those Gallic warbands supported by more cavalry. However, I wonder based on the evidence in this book, if the army lists full of impetuous heavy swordsmen is correct for the later period.

|

| 28mm Gauls from my collection |

No comments:

Post a Comment