No, it's not a typo. I do mean 1940, not 1916. In 1940, before the invasion of France, the Allies were looking for a way of attacking German interests, without turning the Western Front into another WW1 horror. The Balkans were essential to Germany as a source of raw materials, particularly oil and chrome.

The Allies also wanted to support their allies in the region including Yugoslavia and Greece, by forming them into an effective Balkan Entente, which could resist Germany and possibly Italy - although the British hoped to keep Italy neutral. The problem with this plan was the enmity between many Balkan states, notably Bulgaria and Turkey. They all had revisionist claims to each other's territory.

The French were the primary driver of this policy. At the Supreme War Council, the French premier Daladier stressed 'the importance of maintaining an Eastern Front' and said that some tangible evidence of Allied intention to help the Balkans, 'such as the despatch of a force to Salonika or Istanbul', would have a very steadying effect. Chamberlain was much less keen. He argued that only in the case of a German attack in the Balkans, with Italy neutral, should an Allied defensive force be landed in Salonika. And then only if Greece asked for it and Italy agreed. This was not very likely and as events were to prove, the idea that the allies could organise and land a significant force in time was hugely optimistic, even pre-Blitzkrieg.

This did not discourage the French General Weygand who had been engaging with the general staffs of several Balkan states. The British Chiefs of Staff, in a 'Report on the Strategic Situation in South-East Europe and the activities of General Weygand', concluded that Weygand had “gone beyond the policy which had been agreed between H.M.G. and the French government”. At the War Cabinet on 30 November 1939, the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax insisted that Weygand should be 'dissuaded' from disturbing 'the present equilibrium' - mainly the Italians.

The Yugoslavs were eager to co-operate with Weygand because Salonika was a vital port for them. Weygand told them in December 1939 that it was necessary to prepare a base at Salonika and that five divisions were needed for the purpose. The Prince Regent Paul was less keen, as the French had only three divisions in Syria, whereas the Germans had some 48 available for operations in the Balkans. After Anschluss, the Germans were now on Yugoslavia's northern border. He also disliked the French trumpeting these discussions in the media.

It also frightened the Bulgarians against the Allies because support for Romania might entail marching across Bulgaria. The British Minister, George Rendel, wrote later: “it is ... no exaggeration to say that during the first six months of the war the Bulgarians genuinely believed that their neutrality was less likely to be violated by Germany than by the Allies.”

The Greeks were more enthusiastic, General Alexander Papagos, in January 1940, gave the British the impression “that he definitely considered himself and Greece as being our allies in all except the word”.

The split between the French and British widened when Weygand started signing himself 'Commander in Chief of the East Mediterranean Theatre of Operations'. They hoped that hard military facts would restrain the French. Elizabeth Barker in her book ‘British Policy in South-East Europe’ summarises the military requirements:

“As on 19 January the Chiefs of Staff approved an aide memoire which argued that 'a minimum force of some 20 to 24 Allied divisions' would be needed to cover Salonika and prevent enemy penetration past Salonika. The Greeks had offered to supply 10 Greek divisions, an offer which the British did not accept at its face value and this meant that, since any available British forces would have to be earmarked for defence of Turkey, the French would have to provide 10 to 14 divisions; and the British did not think the French could provide them. In any case the British felt they had a power of veto since, as the Chiefs of Staff pointed out, French ability to land forces depended on the British producing the necessary ships.”

The French held secret staff talks in Greece and Yugoslavia and had been authorised to inspect Greek aerodromes create Allied supply dumps. The Yugoslav General Staff had handed over information on communications, transport and airfields.

The military disaster in Norway did not quench French enthusiasm for a Salonika front, but it strengthened British opposition. However, the collapse of France resulted in Weygand's recall to France, and so the British position triumphed by default. They were always more interested in safeguarding Mediterranean sea routes that defended Egypt and the Straits. While there was concern over Weygand’s role in what the British felt was their sphere of interest, there was a genuine belief that the plans were unrealistic.

It is interesting to speculate what the British reaction might have been if Churchill was Prime Minister. Later in the war, he championed the Balkans as an alternative route into Europe. Hitler was undoubtedly concerned that the allies would take this route, as he said, 'Salonika had been the beginning of Germany's defeat last time.”

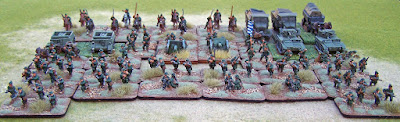

For wargamers looking for another use for those French and British early war armies, this is an interesting ‘what-if' campaign, which is at least based on some actual planning. It is also attractive for my current Royal Yugoslav Army project, and I already have the Greeks. Mind you, if this project is to be completed for our game at the Falkirk Carronade show in May, I will need to do more painting and less research in the National Archives! Another rifle squad and a medium mortar completed, but much more to do.