He joined the Suffolk Regiment in June 1957 with all the enthusiasm of conscripts the world over. He had decided to get it out of the way before going to Cambridge, and while not in favour of National Service, he concludes that “it changed me completely and did me some good. The best education I ever had….”

The Suffolk Regiment was based near Nicosia and did the full range of anti-insurgency duties. From hunting down terrorists to riot control and some efforts to win ‘hearts and minds.’ The strategy for the latter was, to put it mildly confused. The Governor’s peace-seeking policy was in contrast to the robust military strategy. This was never resolved, and as a consequence, neither plan worked. Bell describes operations as like the poll tax: everyone suffered equally through collective punishments and internment without trial. The irony was that internees, as political prisoners, were better housed and better paid than the 35,000 soldiers.

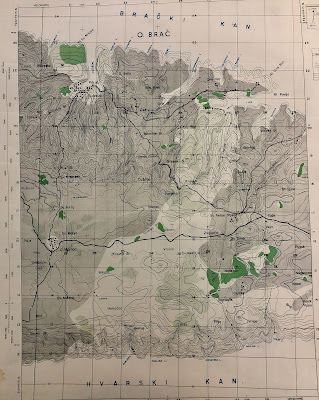

As the Greek Cypriot EOKA forces led by George Grivas stepped up their campaign against the British, Turkish Cypriots and their Greek political opponents on the left, the island drifted into a de facto partition. The seeds of the Turkish intervention were sown in the intercommunal violence of 1958.

Bell’s commentary on military life is entertaining, not that there was much entertainment! This was the ‘old army’, and most soldiers were accommodated in tents that leaked when it rained and fried them in the Cyprus heat when it didn’t. Being an NCO required a loud voice and a wide range of the vernacular, although Bell (who at least didn’t have the voice) managed the rare feat for a National Serviceman of being promoted to sergeant before the end of his tour. Astonishingly, there were 19 military bands on the island.

His more recent research shows clearly that when he arrived in 1957, the army was convinced it was winning. When he left in 1959, there could be no such illusions. His more recent research included a successful battle to get the official history and the Harding Memorandum released under Freedom of Information law, which gives a fresh insight into the muddled policy and poor practice. Detainees on release were encouraged to migrate to the UK. A pretty extraordinary approach as the Special Branch were effectively saying people who were deemed to be a threat in their own country should settle in ours. In practice, most were not a threat anywhere, and they have been some of the most successful immigrants.

371 British servicemen lost their lives in this colonial mess, although of these, 105 were killed in action. As the army’s Director of Operations put it in his final report, “The lesson of Cyprus, therefore, is that a subversive yet nationalist organisation is not destroyed by an assault on the ordinary people.” A lesson all too often forgotten since then!

I am staying in Cyprus this week. Today I visited the Greek Cypriot ‘Monument of Memory and Honour’. It marks the spot where Grivas landed to direct and organise the EOKA campaign. The monument and small museum is just north of Paphos, today a busy tourist area, but then a secluded coast ideal for smuggling weapons from Greece. There is a fine statue of Grivas and a monument that marks the landing spot. The small museum houses the caique, St George, which was used to smuggle weapons in from Greece until the British captured it and its crew.

There is a bit about Grivas and the EOKA campaign. Unsurprisingly, there is no mention of Grivas’s ugly back story during WW2 when he was more interested in fighting the communists than the Germans, to the point of near collaboration. But otherwise, there are photos, some weapons and the caique.